Story so Far: Original heater concept is a no-go as copper tubing can’t absorb/hold/make use of enough heat. Currently awaiting steel block as alternative. Sunrise lamp is unaddressed as of yet but parts are present.

TL;DR: Digital screens let you keep writing when there’s no space left, this can get messy. Digital screens flicker but our brain blurs the world around us to suit itself. Time is pretty crazy, right?

Notice: This ended up very long and took an age to write. Future posts to be planned out better and split into smaller, more frequent ones. Just a bit carried away with the subject matter is all.

Ever tried to take a photo of a digital screen? How come your eyes see 08:20 but your photo is just a blank screen? Or how come there’s black lines going through your photo of a TV screen? Well, Let Me Blow Ya Mind. And also take a meandering route to explain how I’ll make “non-dimmable” bulbs dim/brighten. Basically, a digital clock works like:

>>Check time

>>Clear screen

>>Reset cursor

>>Display time

>>Repeat forever [Forever ever? Forever ever?]

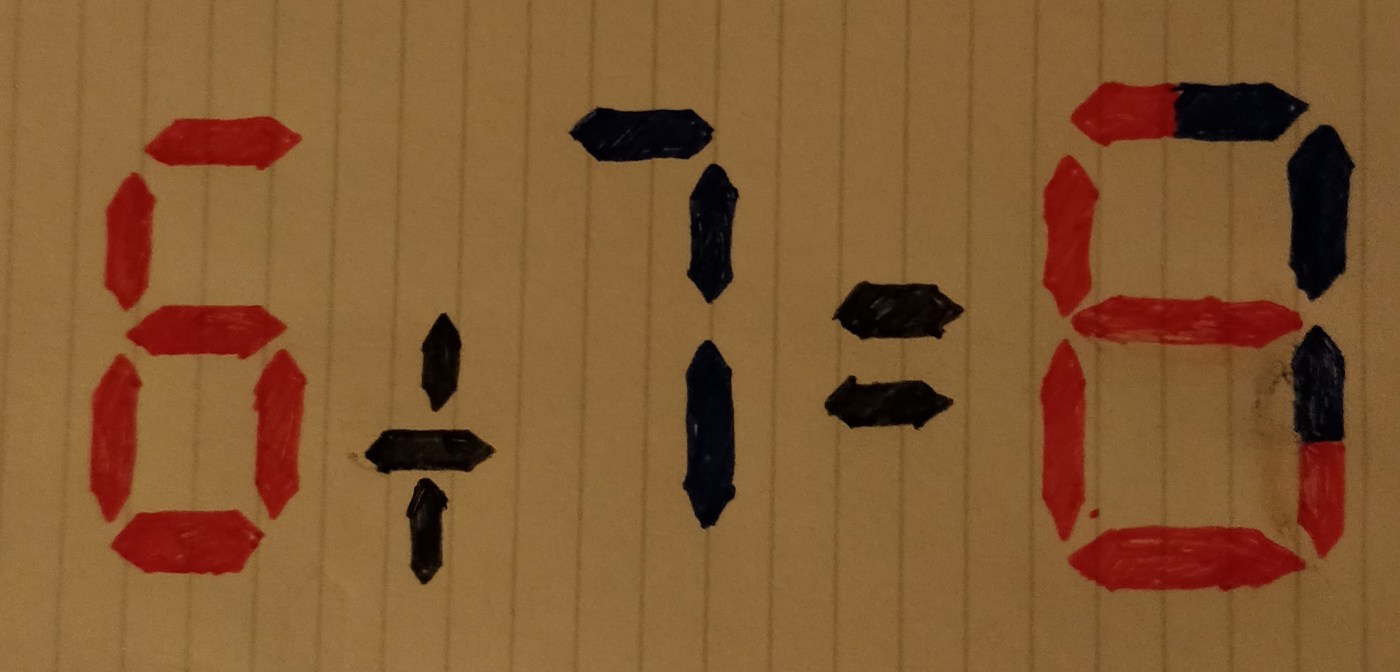

Clearing the screen is absolutely essential every time in case the time changes – if you try to write a 7 in a position where there’s an uncleared 6, it’ll end up as an 8; eventually the entire screen will just read 88:88 forever and this broken clock won’t ever be right, never mind twice in a day.

Resetting the cursor is another crucial part, it’s the same as pulling the carriage return lever on a typewriter except there’s no satisfying mechanical process or rewarding ‘ding’ to announce to the world that you have crafted yet another page-width of art. Typewriters also include a lock that prevents you from typing on at the end of a line and ensures you actually hit the carriage return lever, without such a lock us idiot humans would likely try to type on at the end of a line and shift the carriage to the left one too many times. That would fling the carriage from the typewriter, casting it out of its homely cradle and into oblivion and you better believe it won’t go quietly either, dragging your page of so-called art with it – a spite-fuelled punishment for your ignorance.

Now the type hammers will still strike the ribbon and stamp out their impression in thick, black permanence but there’s no paper to print on. And so, the letter-shaped manifestations of viscosity are projected into the wind, at the mercy of Aeolus. At their most ruinous these letters may land on a nearby book and construct upon it destructively, ruining the literature’s original meaning. At their most harmless, they may land on the reem of paper next to the typewriter, attempting to author a composition of their own.

Point being, digital screens don’t have such a lock. If you attempt to keep writing after the end of the screen is reached, the program will just throw the letters wherever it pleases. Their new allocated address could represent a random spot on the screen, which isn’t so bad, however, if the program is feeling especially malicious it could write them to a part of the memory which houses something important. Something like how long I want the program to run the heater for – for obvious reasons, this would be a disaster*. So it’s important to reset the cursor to the left [to the left].

The problem created by all this is that digital screens spend a not insignificant amount of time not displaying what they’re supposed to be displaying. Cameras with a high enough shutter speed have a fair chance of catching the screen while it’s blank or in the middle of being populated. TV’s do something similar but split their screen into smaller, more manageable horizontal strips and refresh each of them with their share of the next frame. That explains why TVs can appear to have black stripes across them in photos. I’m pretty sure there’s more at play than that but this is where my interests end with it for now. How come we don’t see screens refreshing with our eyes? This is the interesting bit, it’s also where my writing gets a little scatty because I’m overwhelmed with the implications of the topic, I will return to this topic with a more coherent narrative some day.

Gamers will know that humans view the world at about 60 frames per second** – that is, our brain takes a sample of the landscape of light around itself, using our eyes, every 60th of a second (Not quite true, see**). This is fast enough to make us think we’re seeing everything, all the time. Yet we don’t see screens flickering on and off all the time. Well, the screens flicker much faster than every 1/60 seconds and when that happens, all the things in between our samples ‘blur’ together. You can demonstrate this with your phone – decrease the shutter speed and photos can be made to appear blurrier, which is useful to capture motion, blurring something moving fast or blurring the background to convey movement in a still image is no doubt something you’ve seen and appreciated before.

Slideshow: ‘Sea’ the effect of decreasing shutter speed while photographing a video of waves. Longer exposure time means more of the frames blur together and the sea appears smoother/calmer (picture 2 vs. picture 3). Picture 1 shows a very fast shutter speed capturing the horiszontal lines of pixels which are being cleared/altered to show the next frame. Picture 4 shows what happens with a very slow shutter speed. Too much light is blurred together and it just appears as a bright mess.

So, when a light (or screen) flickers on and off faster than 60 times per second, the in-between bits blur together.*** For example, if you flicked a light on and off very quickly, your brain would blur the on and off states between samples and actually see a light that was on all the time but only at half brightness. Similarly, as long as a screen displays what it’s supposed to most of the time, that’s what you’ll ‘see’. This is very useful. See, my LED lamps which I want to use by gradually brightening them, mimicking a sunrise, well, they state explicitly on the box that they are “non-dimmable” – which also means they are non-brightenable; bummer. However, by switching them from full brightness to zero brightness very quickly I can make sure they blur to look like they’re at a certain in between brightness. By varying the ratio of the time the bulbs spend fully on to the time they spend fully off (duty cycle for the initiated), any brightness can be exhibited – assuming the bulbs are observed by a human. Of course, I can’t do this manually but my Arduino, which controls the lights, can flicker them for me very quickly – quite possibly up to millions of times per second if I ask it to. I believe it switches them a few hundred times per second when I don’t make any special requests though and that’s good enough. A good camera might have shutter speeds fast enough that when it snaps a picture of my bulbs they will only ever appear as either fully on or fully off, with the probability of each varying based on the duty cycle. The brighter the bulbs, the more chance of snapping a shot of them fully on****.

It’s pretty crazy that we only observe the world at 60 frames per second, but imagine a world where we truly saw everything in front of us all the time, a world where we didn’t blur the in-between bits. Just a petrifying amount of information at all times entering our brains through our eyes – you would essentially be viewing the world in slow motion. But you still wouldn’t be able to think any faster – birds see in “slow motion” so they can observe and dodge obstacles while flying all gas no brakes style, for us slow-moving humans though, it isn’t really that useful of a tool.

It’d be pretty cool if we could give ourselves an adaptive shutter speed by blinking though and process visual stimulation as we see fit – slow our perception down when driving at high speeds, speed it up when looking at something frighteningly chaotic but harmless – could turn a flashing light into a constant light and avoid photosensitive epilepsy incidents. This would mean blinking 59 times a second to match our current speed of vision, however. Still a nice thought experiment.

Still, the prospect that the “shutter speed of your eyes” determines your perception of time is a very interesting area, particularly since it varies from person to person naturally – research is also trying to pin digital screen use to slowing down our shutter speed – it’d be interesting if that has anything to do with other research claiming reaction times are getting worse since digital screens became so commonplace. The technical term for the “shutter speed of the eyes” is the “flicker fusion threshold” or “critical flicker frequency” by the way. I’ve only just been introduced to it while researching how my LEDs worked for this very blog post but I am enamoured with the concept. Once I make it through a few papers/articles/videos on the topic and finish writing about this alarm clock project you can bet there’ll be a full-on post based upon it. I did say in a previous post that I would find a better, more abstract way to discuss people’s unique perception of time and a story loosely based on flicker fusion thresholds might be it. It does beg the question “what about blind people?” but I don’t have the answers to that yet. Obviously, optical stimulus isn’t the only thing we react to and gauge time from but it is pretty intrinsic to how we (people privileged with the sense of sight) perceive the world.

Food for thought: Higher shutter speed means less light enters the lens to be blurred together. Perhaps a lower critical flicker frequency (shutter speed) means observing the world as a more vibrant place with more light in every frame. Conversely, a higher value means a dimmer world view – flies have a critical flicker frequency 4 times that of humans – is that why their eyes are made up of so many lens-like panels and bulge out? A complicated biological balancing act?

*I’m not sure what exactly happens when writing to addresses that don’t exist, but I’d be confident it’s at least theoretically predictable. I feel like all memory is fair game but maybe not. Might be conflating using pointers and addresses cautiously with writing to peripherals cautiously and that might not be accurate, I’m not sure, but I’ll err out of apathy and err on the side of caution.

** 60Hz is troubling. I don’t think we actually sample our environment at 60Hz. I think we actually sample at 25Hz but certain other quirks of the optical sensing system make it appear as 60Hz. The entire scientific field is insanely complicated, what I’ve said would hold water in a conversation but keep an open mind to people expanding on/correcting it.

***Things might need to flicker faster than just “faster than 60 Hz” I think. Pretty sure Nyquist-Shannon sampling theory would come into play meaning for proper blurring to take effect it would need to be 120Hz – but also the 60Hz figure may take that into account, from context I think it does.

****I realise I’m talking about using pulse-width modulation as if I’ve just discovered fire but I’m trying to convey just how cool it actually is when you don’ take it for granted.